Food Colonialism: How the Norwegian Salmon Industry is Hurting Food Security in West Africa

6 Mins Read

A new investigation reveals the adverse effects of Norwegian farmed salmon on malnutrition, food insecurity and loss of livelihoods in West Africa.

Seafood producers in Norway – the world’s largest supplier of farmed salmon – are driving up to four million people in West Africa towards food insecurity and nutrient deprivation, according to a new study by agrifood campaigner Feedback International and a coalition of West African and Norwegian organisations.

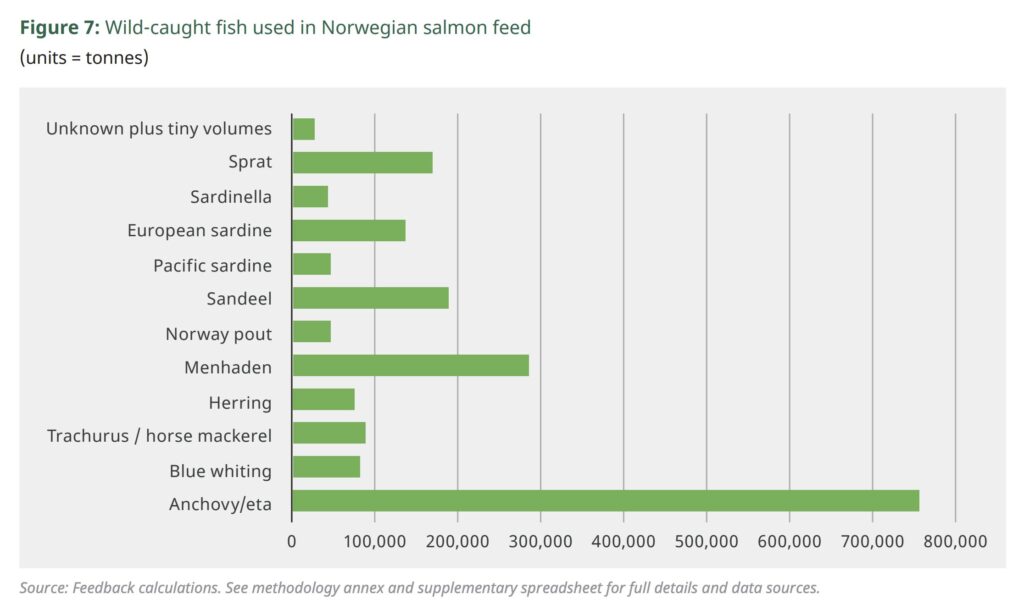

Titled Blue Empire, the report reveals that nearly two million tonnes of wild fish are being extracted annually from major farmed fish and aquafeed producers, which include Mowi, BioMar, Cargill and Skretting. Of these, 75% of species are usually eaten, while the rest are critical for the ecosystem. But most of these fish are being turned into fish oil and meal – key feed ingredients for aquaculture and livestock.

According to Feedback’s calculations, Norwegian salmon’s ‘feed footprint’ makes up 2.5% of global marine fisheries catch, and the country’s annual output of farmed salmon is 27% lower than the volume of wild fish needed to produce the fish oil used by its salmon industry as feed.

A significant portion of fish oil is imported from Northwest Africa, a region suffering from acute food insecurity, and these could have provided four million people in the area with a year’s supply of fish – but instead, it was turned into fish oil to feed farmed salmon for the European market, an act dubbed “nutrient colonialism”.

“For an industry that is so vocal about feeding the world, it certainly is quiet about the fact that it uses millions of tonnes of wild marine resources from around the globe, including from food insecure regions such as West Africa, to feed to its farmed salmon,” said Yves Reichling, a project manager of Feedback’s West Africa programme.

Taking nutrients away from those in need to feed the wealthy

Globally, 11 of the top 20 farmed salmon producers are Norwegian. These companies occupy the first four spots on the list too, accounting for half of all production. Additionally, Norway is one of the main fish suppliers to the UK, accounting for 44% of the latter’s salmon consumption in 2022. The Nordic country’s farmed salmon is available on the shelves of retailers such as Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Lidl and Asda, as well as restaurant chains like Wagamama.

In fact, farmed salmon is now one of Norway’s most important export industries, behind only the oil and gas sector. But while many of these producers claim to be positively contributing to food security, they’re really selling to high-income countries where requirements for protein and micronutrients are already being met. The report further accused Norway of a “startling lack of policy coherence”, in reference to its international development policy to increase food security in areas including sub-Saharan Africa, where 84% of people can’t afford a healthy diet, and 274 million were undernourished as of 2020.

The small pelagic fish (also called forage fish) targeted by the feed industry contain key micronutrients like zinc, iron, calcium, vitamin A and omega-3 fatty acids, which are critical in West Africa, where more than half of the female population suffer from anaemia. These micronutrients are vital for children in their first 1,000 days of life, as well as for pregnant women and nursing mothers. But in sub-Saharan Africa, 62% of children under five lack essential micronutrients and consume just 38% of their recommended seafood intake.

Termed the “fish of the people” locally, they have provided about 65% of the animal protein consumed by the people in Senegal and the Gambia. In Senegal alone, fish consumption declined by 50% between 2009 and 2018, due to a lack of availability of these pelagic fish. Meanwhile, all of Mauritania’s fishmeal and oil is exported, largely as feed, with 90% of the latte destined for European salmon.

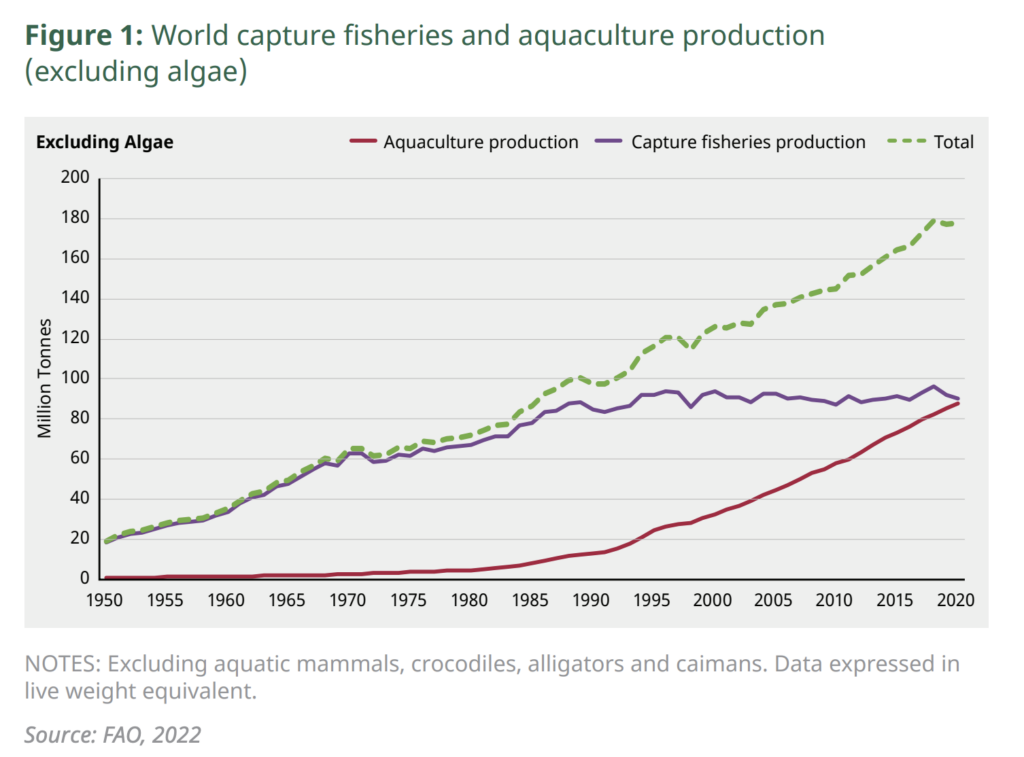

The global rise in demand for salmon has meant that this carnivorous species consumes 44% of the world’s fish oil, according to DeSmog. But despite its heavy reliance on wild-caught fish, salmon only accounts for 4.5% of global seafood production by the aquaculture industry. In total, half a million tonnes of West African fish are being turned into feed ingredients globally every year, an amount that is enough to feed 33 million people – that’s all of Senegal, the Gambia, Mauritania and Liberia combined, with some change.

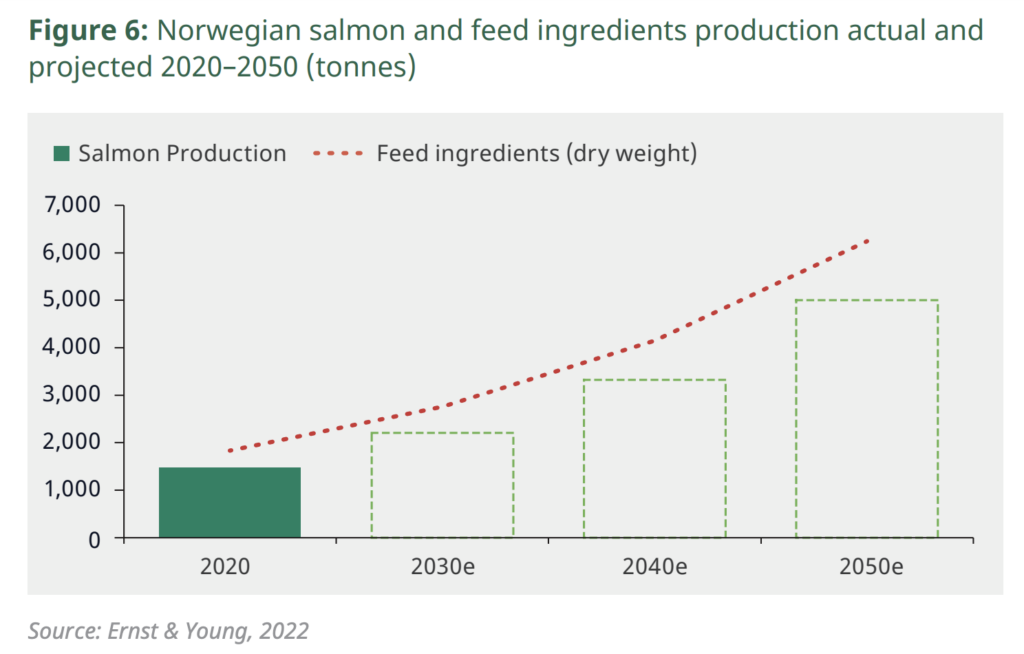

Norway now aims to triple its farmed salmon output by 2050 to reach five million tonnes. Even though many of these salmon and feed producers have taken sustainability pledges, their adoption of alternatives (like algal oil and single-cell proteins) to replace wild-caught fish in feed remains minimal.

“While salmon companies claim their ‘blue revolution’ will contribute to global food security by feeding the world, the rapid expansion of industrial aquaculture is fuelling a modern-day colonialism, or food imperialism,” said Feedback campaigns manager Natasha Hurley. “Despite mounting hunger and malnutrition in West African countries, corporate sustainability initiatives are failing to protect West African communities from hunger and malnutrition linked to the voracious appetite of the salmon farming industry for wild fish.”

What Norway’s salmon industry can do

The Feedback report pointed to a lack of supply chain transparency in the industry, especially the absence of standardised and comparable data. Few companies share details about the individual factories they source from in West Africa, hindering the traceability of their operations’ environmental and socioeconomic impacts.

The report’s authors lay out demands and recommendations for the Norwegian aquafeed industry and government, respectively. For the former, it asks producers to stop sourcing fish meal and oil from areas where their production is driving food-feed competition and exacerbating food insecurity, particularly vulnerable West African countries.

Salmon producers also need clear policies around responsible sourcing of feed ingredients, and must disclose details of its aquafeed sourcing (like volumes, locations and species) transparently and consistently. Feedback additionally asks producers to put an end to the use of whole wild-caught fish in feed.

For the government, the report suggests it mandate full transparency on feed coursing at all stages of the aquaculture supply chain, ensure domestic producers’ sourcing and activities don’t run counter to Norway’s global development policies, and halt the overall growth of the country’s salmon farming industry.

“This is big business stripping life from our oceans, and depriving our fishing communities of their livelihoods. The science is clear, it will soon be too late. They must stop now,” implored Dr Aliou Ba, senior oceans campaign manager for Greenpeace Africa. “These industries established in West Africa use fish to produce fish meal and fish oil to feed animals in Europe and Asia, while the African population needs this fish to feed themselves.”

Elise Åsnes, president of climate non-profit Spire, added: “Norwegian politics on food security must be coordinated at home and abroad. We cannot have a Norwegian salmon industry based off the use of food resources of other food-insecure countries. What this report shows is just another way of taking the food out of the hands of poor countries.”