7 Mins Read

The unaccounted costs of the global food system on human and planetary health amounts to $15T a year, according to a new report, which predicts contrasting futures based on current trends and transformation pathways, and suggests the best way forward.

In what is one of the most ambitious studies of food system finance, scientists and economists from the Food System Economics Commission (FSEC) – a joint initiative by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), the Food and Land Use Coalition, and the food non-profit EAT – have revealed the true cost of our eating habits on the planet and human health.

The global food system today caters to a population that has doubled from 1970 levels, but the unaccounted, true cost of the burden they place on people and the climate is $15T, which is equivalent to 12% of the total GDP in 2020. These costs comprise health and its negative effects on labour productivity (estimated at $11T), the environment and the detrimental impact of our food system on the climate, and the prevalence of poverty, which tends to be higher in the agriculture sector due to low incomes.

“The costs of inaction to transform the broken food system will probably exceed the estimates in this assessment, given that the world continues to rapidly move along an extremely dangerous path whereby it is likely to not only breach the 1.5°C limit, but also face decades of overshoot, before potentially coming back to 1.5°C by the end of this century,” explained Johan Rockström, principal of FSEC and director of PIK. “Overshoot, even of 0.1-0.3 degrees, will add massive social costs across the world.”

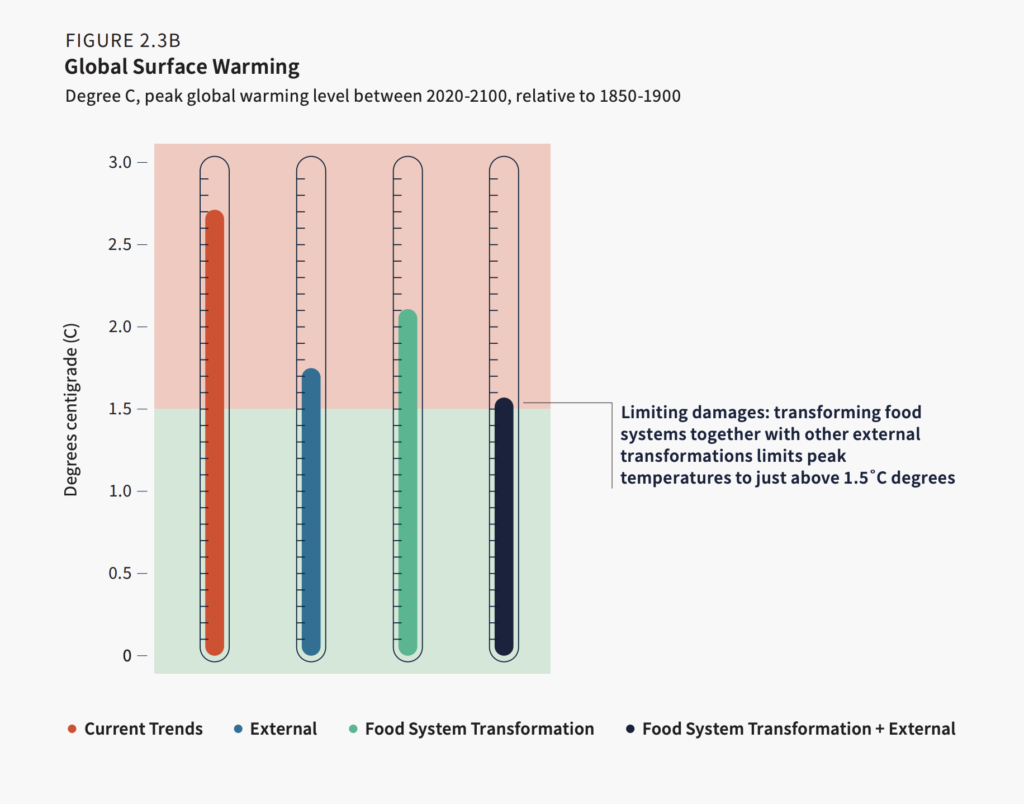

As it stands, even if countries follow through on their national climate action plans, the food system’s trajectory would continue to be unsustainable, producing emissions that will lead to an increase in global temperatures by 2.7°C by the end of the century, compared to preindustrial levels.

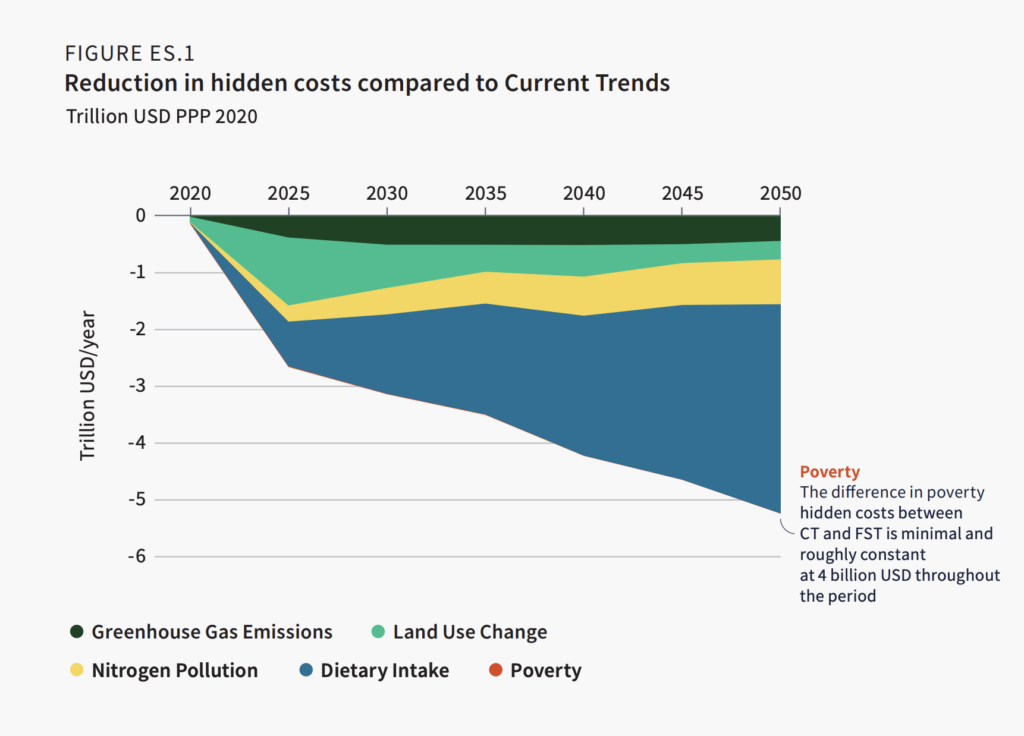

However, a transformation of the food system could yield economic benefits between $5T and $10T a year. To illustrate the differences, the FSEC compares two scenarios, one based on current trends, and the other on food system transformation, to show what the future of our planet and health could look like.

Where we’d be if we follow current trends

The result of a four-year investigation, the FSEC’s report reveals that if current trends continue, food insecurity will leave 640 million people (including 121 million children) underweight by mid-century, but the global adoption of unhealthy diets would conversely lead to a 70% increase in obesity, reaching 1.5 billion or 15% of the global population in 2050. The costs of treating the health effects of being overweight will rise from $600B today to almost $3T by 2030.

We’re already wasting a third of all food produced, but if these patterns persist, per capita food waste will increase by 16%, reaching 76kg of dry matter per person in 2050. Meanwhile, cultivating food will become much more susceptible to climate change, with extreme evens likely increasing. Rising food prices will heighten poverty and hunger, leading to social tensions and the introduction of measures to limit trade.

Deforestation will erode a further 71 million hectares of natural forests by mid-century, an area equivalent to 1.3 times the size of France. This will have far-reaching implications for carbon emissions and biodiversity loss. And nitrogen surplus from agriculture and natural land will increase too, from 245 to 300 tonnes annually, polluting water, destroying biodiversity and undermining public health.

“Rather than mortgaging our future and building up mounting costs that we will have to pay down the line, policymakers need to face the food system challenge head-on and make the changes which will reap huge short- and long-term benefits globally,” said Dr Ottmar Edenhofer, co-chair of FSEC and director of PIK.

What a food system transformation could do

On the other hand, the FSEC found that food systems can be an economic boon, with better policies and practices bringing major benefits. Although a hypothetical scenario for now, it would mean undernutrition will be eradicated by 2050, preventing 174 million premature deaths due to diet-related chronic conditions. The impact of changing diets on consumption and (indirectly) land use would account for 70% of the benefits of transforming food systems, while cutting food waste by 24%.

The world’s 400 million farmers in 2050 will enjoy a sufficient income as a result of increased productivity and supportive policies. Agriculture will become less labour-intensive too, meaning 75 million on-farm jobs can be reallocated to other food system segments. A shift to sustainable agricultural production methods would reverse biodiversity loss, reduce demand for irrigation water, and almost halve nitrogen surplus from agriculture and natural land.

Speaking of which, 1.4 billion hectares of land could be protected, and a further 200 million hectares afforested and opened to planet-friendly economic uses. The food system would become a net carbon sink by mid-century, helping limit post-industrial temperature rises to 1.5°C (alongside sustainability shifts in other sectors). This transformation would play out differently across the world – in south and southeast Asia, healthy dietary patterns would mean a notable shift in fruit, vegetable, nut and legume consumption, while in high- and middle-income regions, there would be a drastic drop in the intake of animal-derived food.

The report’s authors quantified the costs of this food system transformation, estimating them to be between 0.2-0.4% of the global GDP per year. “The food system has immense potential as preventative medicine for both people and planet, but is currently causing widespread damage,” noted Gunhild Stordalen, principal of FSEC and executive chair of EAT. “To avert this tragedy, global policymakers must revamp fragmented policies and regulations, utilising the food system’s power for positive change.”

How we can transform our food system

The FSEC’s findings mirror a report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization in November, which found that the hidden costs of agrifood systems amount to $12T annually, with 70% of costs related to health, and a quarter linked to the climate. The FSEC found that transforming the food system would cost between $200-500B a year, which is dwarfed by the potential economic benefits in the multi-trillions.

It suggests five broad strategies to help bring about the change:

- Shifting dietary patterns: There’s no one-size-fits-all approach, but encouraging healthier and more sustainable diets tailored to local needs is the way to go. This would include reducing meat and dairy consumption in many parts of the world – but the FSEC also advocates increasing it in some regions to combat undernutrition, echoing the FAO’s COP28 roadmap. Other suggested policies include sugar taxes, reformulating packaged foods, and regulating the marketing of unhealthy foods to children.

- Repurposing agrifood subsidies: With government subsidies heavily favouring animal agriculture, redirecting finances to improve access to healthy and sustainable diets is key. But doing so could displace production to less efficient countries, so investments to improve productivity are needed.

- Taxing carbon-intensive foods: Governments could tax carbon and nitrogen pollution in food production, and direct resulting income to make healthy foods more affordable for low-income households.

- Investing in innovation: Public sector investment in new agricultural technologies and widening accessibility of existing ones to support smallholder farmers is paramount. This entails digital technologies like remote sensing, in-field sensors, and market access apps, as well as enhancing plant breeding and supporting low-emission farming systems.

- Scaling up safety nets to safeguard the poor: It is vital to develop safety nets to make the food system transformation inclusive and feasible. Countries could target limited transfer resources on children, whose nutritional needs are critically linked to their lifetime achievements, and mobilise more resources to put more comprehensive safety nets in place. Targeted investment in productive infrastructure, skills and access to finance for the most vulnerable – like women farmers – is equally important, as is mitigating knock-on effects like food price hikes and job losses.

“This research shows that equitable transformation of global food systems can bring benefits to the health of people, planet and economies,” said WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. “By encouraging and increasing access to sustainable healthy diets, world leaders have an opportunity to save millions of lives, trillions of dollars, and the natural resources on which we depend.”

“It’s clear what needs to change, and yet it remains easier and cheaper to produce and eat food that is severely damaging to our health and the planet,” added Henry Dimbleby, author of the UK’s National Food Strategy and co-founder of food chain Leon. “The economic burden of doing nothing is so great, that if we governments do not heed this call, we will end up not just sick, but impoverished.”

Echoing this sentiment, food writer and journalist Michael Pollan said: there is “no longer time to delay the inevitable”. “The restructuring of food systems is indisputably one of the greatest opportunities we have to reverse decades of damage to both the planet and to human health,” he noted.

Summing up, FSEC principal Rockström said: “The only way to return back to 1.5°C is to phase out fossil fuels, keep nature intact and transition food systems from source to sink of greenhouse gases. The global food system thereby holds the future of humanity on Earth in its hand.”