Climate Finance Programme for Developing Nations is Funnelling Billions Back to Rich Countries

7 Mins Read

Rich countries have been sending climate funds to developing nations via programmes that financially benefit themselves, a new investigation shows.

In 2009, at COP15 in Copenhagen, developed nations pledged to send $100B a year to help low- and middle-income nations cut emissions and adapt to climate change. They finally met the annual goal in 2022, two years after the original deadline.

But really, while these funds are meant to help developing countries deal with climate change, the schemes have come with strings attached or interest rates that channel money back into the lenders’ economies, according to a new investigation by Reuters and Big Local News, a Stanford University journalism programme.

The news agency analysed data from the UN and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to find that wealthy nations have loaned at least $18B at market interest rates. This is not the norm for climate and other aid-related loans, which carry low to no interest.

Additionally, another $11B in loans required recipients to hire or purchase materials from companies in the lending countries. Similarly, at least $10.6B in grants had similar strings attached, mandating developing nations to hire companies, non-profits and public agencies from specific nations to do the work or provide materials.

Providing loans at market rates or with such conditions attached means money meant to help developing countries just ends up back in the hands of affluent ones, something Liane Schalatek, associate director of think tank Heinrich-Boll Foundation Washington, called “deeply reprehensible”. By doing so, rich economies are contradicting their own concept of compensating poorer ones for the environmental damage they’ve caused through long-term pollution, according to multiple climate experts who spoke to Reuters.

Focus on loans over grants crippling debt-ridden nations

Roughly $353B was paid to poorer economies between 2015 and 2022 as part of the COP15 pledge, a sum that included $189B in direct country-to-country payments. But 54% of this direct funding came in the form of loans instead of grants.

Grants that require participants to hire suppliers from lending countries are less harmful than loans with the same conditions, as they don’t require repayment. Sometimes, when recipient countries lack technical expertise, these arrangements can be necessary too. But at other times, they benefit rich countries at the expense of the vulnerable nations they’re supposed to help.

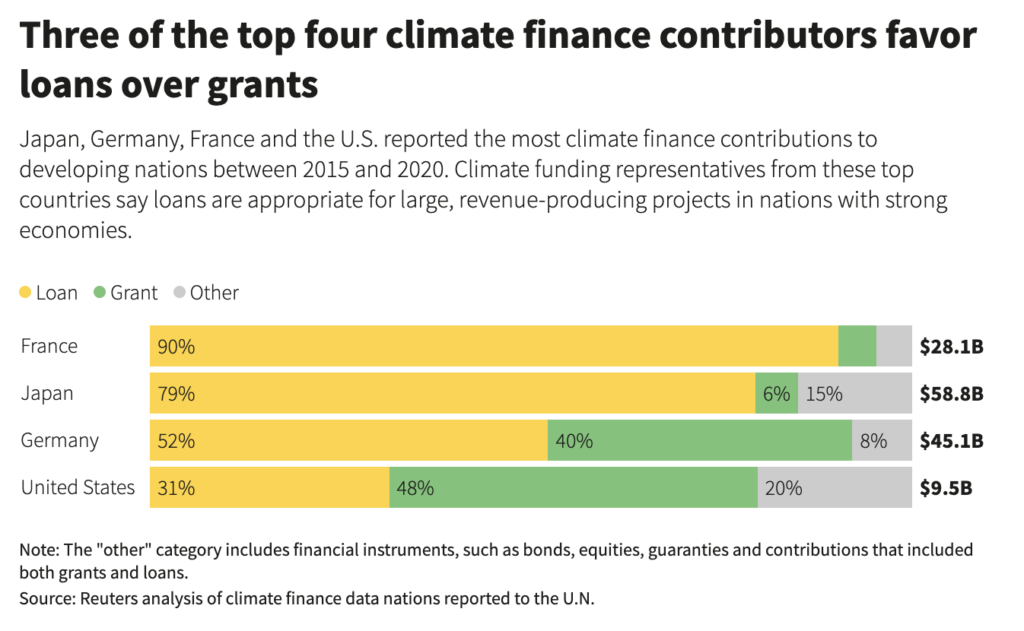

In fact, three of the top four climate finance contributors prefer loans over grants. This includes France (90%), Japan (79%) and Germany (52%). The US, meanwhile, has provided 31% of its funding in loans, and 48% in grants.

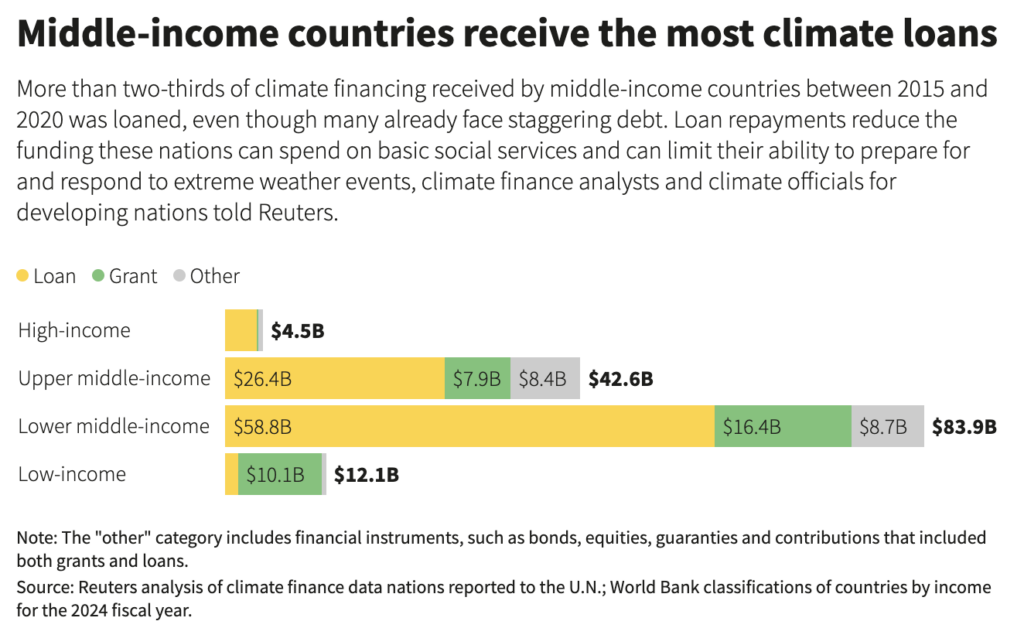

Middle-income countries are the largest recipients of climate funding, and receive the highest share of loans too. Upper middle-income nations get 62% of this aid in loans, and lower middle-income countries get an even larger 70%. But this is the opposite for low-income states, meanwhile, which receive 83% of their climate funding in grants.

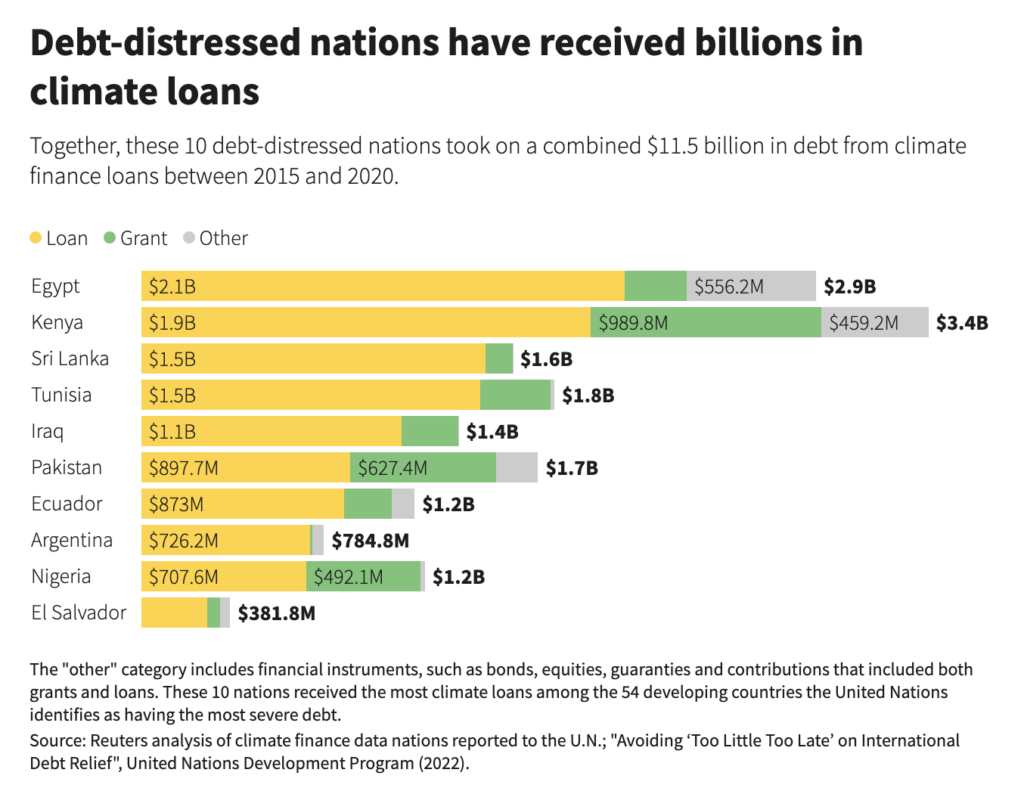

These funding structures mean countries in “the Global South are experiencing a new wave of debt caused by climate finance”, according to Andres Mogro, Ecuador’s former national director for climate change adaptation. Egypt, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Iraq, Pakistan, Ecuador, Argentina, Nigeria and El Salvador are already debt-stressed nations, and took on a combined $11.5B in climate finance loans between 2015 and 2020.

Debt payments limit countries’ ability to invest in climate solutions – a UNDP report from 2022 revealed that over half of the 54 most severely indebted developing nations were also the most vulnerable to the impact of climate change.

Meanwhile, analysts say rich countries are overstating their contributions to the $100B pledge, since a portion of their finance comes back to them through loan repayments, interest and work contracts. “The benefits to donor countries disproportionately overshadow the primary objective of supporting climate action in developing countries,” said Ritu Bharadwaj, principal climate finance researcher at UK think tank the International Institute for Environment and Development.

This comes just as countries are hoping to negotiate a better climate funding package by the end of the year. The UN estimates that to meet the targets of the 2015 Paris Agreement (which aims to limit postindustrial temperature rises well below 2°C), the world needs $2.4T in climate finance each year.

The importance of concessional loans

Japan is the largest contributor to climate finance, providing nearly $59B in funds between 2015 and 2020. But 32% of its loans required borrowers to use some of the money to hire Japanese companies, funnelling $10.8B back to its economy.

For example, Sumitomo Corp and Japan Transport Engineering Co won three contracts worth over $1.3B to supply 648 train cars for electrified rail projects in the Philippines. One of Sumitomo’s sister companies won two other contracts worth over $1B to build rail expansion and station buildings.

But development aid representatives from Japan, France, Germany, the US and the EU say loans allow them to inject much more money than grants. Some stakeholders who have worked on climate issues in developing countries add that loans can be necessary for ambitious climate projects since wealthy nations have allocated limited funding for climate finance, but they added that future pledges should require them to be more transparent about the conditions and offer safeguards against loans that create suffocating debts.

Simon Stiell, executive director of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, has previously implored developed nations to offer ‘concessional loans’, which have very low interest rates and long repayment periods, making them less costly than open-market rates. But 18% of these loans have been non-concessional, including over half of the loans provided by the US and Spain. This is likely an underestimate, as reporting on the nature of their loans is voluntary for affluent nations.

An example of the damage created by non-concessional loans comes from France, which funded $118.5M to build an aerial tramway in Guayaquil, a port city in Ecuador. Since its inauguration, the climate-friendly alternative to congested bridges saw underwhelming passenger numbers, with ridership only a fifth of what was expected. This meant lower revenue and environmental benefits than anticipated.

Early planning documents show that Guayaquil was to pay 5.88% interest, with France projected to earn $76M over 20 years in repayments. While the final interest rate hasn’t been disclosed, the loan debts have added $124M to the Ecuadorian city’s budget deficit. “This is a classic example where a bad loan, which has been given to a country in the garb of climate finance, will create further… financial stress,” said Bharadwaj.

Rich countries’ rhetoric highlights Paris Agreement shortcomings

Representatives of the climate finance agencies of the US, Japan, Germany and France told Reuters they consider how much debt a country is in before deciding whether to offer a loan or a grant.

“A mix of loans and grants ensures that public donor funding can be directed to countries that need it most, while economically stronger countries can benefit from better-than-market rate loan conditions,” said Heike Henn, climate and energy director at the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development in Germany (52% of whose $45B in climate funding have been loans).

Atika Ben Maid, climate and nature head at the French Development Agency, meanwhile, said it offers developing nations low interest rates that would normally be available only to the richest countries on the open market. But as mentioned above, France’s share of loans is the highest of any nation at 90%.

And a US State Department spokesperson suggested that loans are “appropriate and cost-effective” for revenue-generating projects, with grants typically directed to other types of projects in “low-income and climate-vulnerable communities”.

“It should also be emphasised that the climate finance provisions of the Paris Agreement are not based on ‘making amends’ for harm caused by historic emissions,” they said. And while true in the most literal sense, the Paris Agreement does refer to “climate justice” and “equity”, and notes countries’ “common but differentiated responsibilities and capabilities” to grapple with climate change. It also makes it clear that wealthy nations are expected to provide climate finance.

However, the Agreement doesn’t say whether grants should be prioritised over loans, or prohibit developed countries from imposing advantageous conditions. “It’s like setting a building on fire and then selling the fire extinguishers outside,” said Ecuador’s Mogro.

Such investments should “serve the needs and priorities of recipient developing countries”, according to Schalatek. “Climate finance provision should not be a business opportunity,” she said.